Condoms have been a source of American anxiety since 1873, when they were swept up in moral crusader Anthony Comstock’s campaign against pornography. In the mid-twentieth century, condoms were legal, but only sold to married men. Brands such as Sheik, Ramses, and Sphinx were suggestive of hypersexualized Middle Eastern fantasies. Despite their success rates and affordability, many mid-century Americans still found the condom taboo – associated with promiscuity due to their promotion as a way to combat venereal disease among soldiers. Second-wave feminists shifted sexual discourse by publishing material about sex and contraception. The women’s health movement was ignited by the publication of Our Bodies, Ourselves (OBOS) in 1973 (Davis 21-22). Two years earlier, Gloria Steinem and Patricia Carbine founded Ms. magazine, which addressed abortion and domestic violence, bringing feminism into the mainstream. By the 1980s, condom brands with names like Mentor and Lifestyles were marketing directly to women. Even Trojan began advertising in Ms. (Gross). The AIDS crisis brought a new cultural focus to condoms, including a national health ad campaign. The condom itself forms a boundary against contamination. It is the fulcrum of an attraction/repulsion dynamic; this can be traced to the ways in which condoms and their link to sexuality were rendered in visual culture. This article uses visual culture, including military posters and magazine advertisements, to reflect a moral tension over the condom and to trace American attitudes on contraception between World War II and the AIDS epidemic.

This article traces the history of the condom through visual culture, focusing on two historical periods – World War II and the late 1980s – that illustrate shifts in attitudes toward sex and contraception. While the U.S. government’s wartime attention to contraception was a critical albeit brief moment of disseminating candid sexual health information, the 1980s were a turning point when condom information became widely accessible. A stigma has surrounded the condom, which has been associated in the public mind with venereal disease, prostitution and sexual encounters between men. The condom suggests arousal and sexual attraction. Yet it also prevents stigmatized diseases. Women’s magazines initially approached condom advertisements with trepidation, uncertain of how to discuss sexual education, intercourse, disease, and pregnancy. The condom made a comeback in U.S. society during World War II and regained visibility during the AIDS epidemic, which changed the ways in which the American media and consumers understood condoms. Women’s magazines began marketing condoms as empowering and lifesaving. For these magazines, the fear of AIDS was a concern about white women’s purity, an American cause with a long history.

This article reviews three main actors in the history of condom discourse who served as sex educators: propagandists who spread misinformation about venereal disease during wartime, second wave feminists and women’s health authors, and gay rights activists. Advertisers who sought to tap into the women’s market were a driving force behind sex education. These “teachers” of sex (mis)information used varied pedagogies, too: pedagogies of blame and shame in military public health posters; of self-protection for feminists and queer groups, and of consumer-driven self-promotion for ad makers.

This article is informed by secondary literature on contraception and venereal disease history from historians Allan Brandt, Andrea Tone, Linda Gordon, and sociologist Joshua Gamson. Brandt’s social history of venereal diseases since the late nineteenth century narrated the medical, military, and public health responses to disease and Americans’ anxieties about gender, sexuality, race, and social class. Tone’s Devices and Desires: A History of Contraceptives in America, discussed the production, demand, and use of contraceptives from the late nineteenth century to 1970. Gordon’s Woman’s Body, Woman’s Right: Birth Control in America examined birth control controversies from the mid-nineteenth century to later twentieth century abortion arguments, and like Tone and Brandt, traced social and political responses to birth control. Gamson examined access to contraception in the 1930s and 1940s and public debates about HIV during the 1980s. This article will center on U.S. anxieties surrounding the condom, focusing on sexual norms as evidenced by visual culture to demonstrate whose bodies mattered in public and sexual health narratives. This article adds to the existing scholarship, revealing ways in which the visual culture of the condom shows a shift from conceptualizing women as harbingers of disease to seeing them as victims in need of education.

I trace histories of venereal disease, sex education, and national debates about sexual culture, using condom advertisements from Saint Mary’s College’s magazine collection along with WWII venereal disease posters from the University of Minnesota’s Social Welfare History Archives. Studying the changing visual culture surrounding the condom illuminates the ways in which the birth control movement has been rooted in prejudice – against the nebulous group of “others” stigmatized by a certain era. Xenophobia – especially toward foreign women – was rampant during wartime public health campaigns, and backlash over the AIDS epidemic was characterized by fear and homophobia. In other words, visual culture regarding condoms came with a subtext, a “hidden curriculum,” as Peter McLaren would write where the ideas produced implicitly favor certain – generally dominant – groups. This unintended or indirect outcome of education (McLaren 49) transpires in various ways throughout the period. Wartime sexual culture’s hidden curriculum was that women were promiscuous. But later advertisements in the 1980s painted quite a different vision of womanhood by including embodied women who spoke directly to readers about taking control of contraceptive needs. Early twentieth century U.S. sex education privileged men’s sexual desires and protection in narratives about venereal disease (VD), while later narratives warned heterosexual women to protect themselves.

I present the images in this article as a collection of condom visual culture, each image presented to the public with a specific intention. Scholar Shawn Michelle Smith has illuminated the use of archives as “conceived with political intent, to make specific claims on cultural meaning” (Smith 7). She sees primary sources as articulating emotions and feelings, and this is true in condom visual culture. Photographers, artists, and advertisers used images to instill the condom with meaning about bodies and sexuality. Pharmacists, politicians, advertisers, and citizens all debated the meaning of the condom, and together these interest groups created narratives about the contraception that dominated popular culture. To some, the condom would protect U.S. soldiers from syphilis during World War II. To others, the condom combatted public health ignorance in a new era of deadly HIV.

In examining the visual culture representations of the condom, this article considers the intersection of race, gender, and sexuality. My work is informed by Shawn Michelle Smith and Richard Dyer’s framework about aesthetics, memory, and race. Smith explains the role of archival matter in understanding the past: “archives have an ideological function not only in the moment of their inception but also across time, for they determine in large part what will be collectively remembered and how it will be remembered” (8). If we are to decipher “how it will be remembered” from images of the condom, we will see the condom rendered as protective, medicinal, sexual, powerful, and pleasurable. Many condom images in public health poster campaigns and magazine advertisements feature women’s bodies – and white women only. As Dyer wrote in his book White: Essays on Race and Culture, the association between whiteness and ordinariness “means that white people can both lay claim to the spirit that aspires to the heights of humanity and yet supposedly speak and act disinterestedly as humanity’s most average and unremarkable representatives” (223). The popularity of using images of white women reveals a tension between historical reality – that people of every race experienced disease and unwanted pregnancies – and the narrative about birth control presented to consumers: that only white women were worthy of protection.

Tracing Anxiety about the Condom

Condom use became prevalent in the United States after the vulcanization of rubber in the 1840s. They were previously imported from Europe and made with animal organs (Engelman 4, 10). Mass production and distribution of condoms followed, along with mass use of condoms as part of consumers’ sexual health practices (Gamson 265). Yet, social reformer Anthony Comstock leveled the condom industry with his vice campaign. The Comstock Law passed in 1873 made advertisements for birth control illegal. At this point, according to Sarah Forbes, curator of the New York City’s Museum of Sex, “condoms were forced underground. You couldn’t get them in the same way that you had before. After Comstock, because people weren’t able to use condoms, the rate of STDs skyrocketed” (History of Condom). Declaring the condom profane and illegal diminished the condom industry’s reputation; condoms were still associated mainly with prostitution in the early 20th century (Engelman 28).1

The condom was never just a condom – a thin, waterproof contraceptive device that prevents pregnancy and disease. Condoms have a history in the United States of being infused with meaning by different interest groups. Linda Gordon discusses the ways in which physicians addressed “hygiene” – a euphemism for sexual health – in moralistic terms during the late 19th century. One Boston gynecologist wrote that “condoms degraded love and produced lesions” (Gordon 168). This false pronouncement of the condom producing symptoms of a sexually transmitted disease had repercussions; some birth control reformers refused to advocate for condom use during the Great Depression. “One reason for the neglect of the condom was fear of licensing sexual immorality,” Gordon wrote. “The condom was well suited to be, as it indeed became, the chief contraceptive for ‘sinners.’ It was easy to get and required no doctors” (306). Yet it was kept in a male sphere. Women had no place in the selling and distribution of these devices; even up until the 1960s, women faced pharmacists who would sell condoms only to married men (Luker 71).

Venereal disease outbreaks during war changed the usage rates of condoms, even if it was still taboo for many Americans back home. Andrea Tone argues that the sexually transmitted disease (STD) rate among soldiers during World War I and the 1918 Crane Decision (People of the State of New York v. Margaret H. Sanger) allowing doctors to prescribe contraception for preventing disease changed the image of the condom. After 1918, “the condom industry flourished as skins and rubbers marked ‘for the prevention of disease only’ became familiar sights in neighborhood drugstores” (Tone 108). By 1931, the top manufacturers of condoms in the United States produced more than 1.4 million daily (Tone 184). Still, a culture of silence surrounded condoms, even from the American Social Hygiene Association (ASHA), a non-profit organization founded in 1914 by public health reformers dedicated to preventing STDs. The association was reluctant to endorse condoms as an effective defense against venereal disease (Gamson 262). Condoms were still considered beyond the bounds of propriety in society, supporting scholar Michel Foucault’s understanding of sexual repression in The History of Sexuality: “For a long time, the story goes, we supported a Victorian regime, and we continue to be dominated by it even today. Thus, the image of the imperial prude is emblazoned on our restrained, mute, and hypocritical society” (Foucault 3).

Women’s magazines were creative in educating readership about sex and birth control. As scholar Amy Sarch observed, early advertisements in women’s magazines from the 1920s and 1930s spoke to readers about Lysol and cleaning products that doubled as contraception when used with a diaphragm: “Lysol pursues germs into hidden folds and crevices” (Sarch 36). While women’s magazines were not advertising condoms, they featured Lysol and Zonite, a “feminine hygiene product,” or douche, and these advertisements featured white women who were in a “crisis” due to “odor.” Early to mid-twentieth century magazine advertisements often shamed women for body odor, vaginal order, and bad breath with images of worried women.

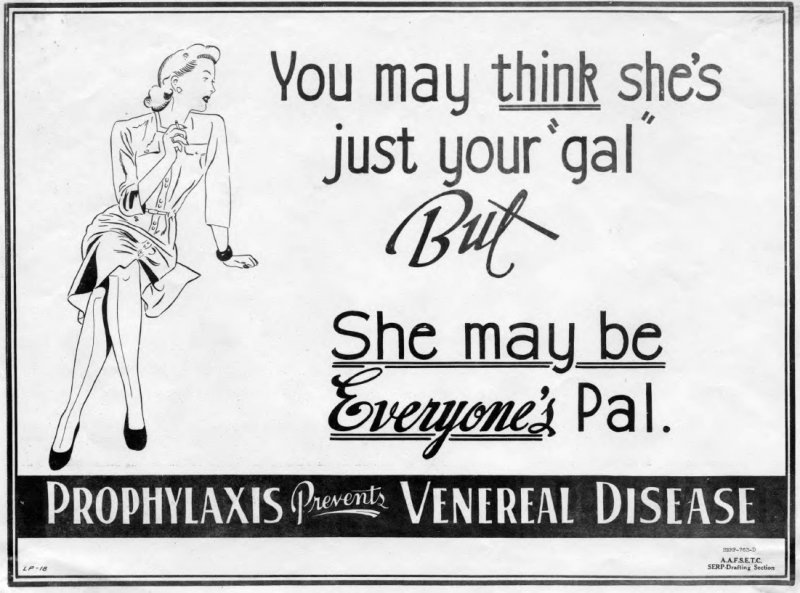

During World War II, the U.S. government published a poster targeting sexually-transmitted diseases among servicemen. The poster featured a white woman with a bob haircut smiling over the caption, “She may look clean — but pick-ups, ‘good time’ girls, prostitutes spread syphilis and gonorrhea. You can't beat the Axis if you get VD. [See Figure 1].” Service members are drawn small in scale as they gaze at a smiling white woman. The faces of the soldiers are not shown – only the woman, who wears makeup and a collared shirt, showing that any woman who looks presentable may, in fact, be a source of disease. Another World War II military poster features the slogan, “You may think she's just your ‘gal’ but she may be everyone’s pal. Prophylaxis Prevents Venereal Disease [See Figure 2].” The poster shows a white woman wearing a dress, pantyhose, and earrings while holding a cigarette. The message is clear: sex was threatening success in the war, but condoms could save the soldier from venereal disease spread by sneaky, sultry women who were carriers of disease.

Scholar Marilyn E. Hegarty’s work discusses a national obsession with women’s promiscuity during World War II, tracking the ways in which women were branded as deviant, even detained and quarantined if they had diseases. Hegarty explains the varied ways women were considered suspect: from the assistant attorney general discussing the need to find “suspected persons” who had “infected members of the armed forces” so that they could be brought in for examinations, to the U.S. Public Health Service studying “promiscuity” – and even the “potentially promiscuous” (70-73). The women who were swept off the streets, or studied by public health experts, were of different races and marital statuses. Often, they were young, Hegarty wrote, and that even women without venereal disease with subject to quarantine (76). This was not the first time in U.S. history that women were treated like sexual suspects, but by World War II, the medical community had long known how sexually transmitted diseases spread through unprotected intercourse. The posters ignored medical evidence to suggest that women – either promiscuous women or prostitutes – were solely responsible for spreading disease. Although the posters targeted women’s purity, the reality was that men often brought disease home to their wives, whose doctors lied to them about their diagnoses to protect the sanctity of the nuclear family. Physicians kept a diagnosis of venereal disease from patients’ wives out of fear that “if the nature of a man’s infection were fully explained to his spouse, many marriages would be terminated” (Brandt 17).

While these public health posters argued that condoms protected soldiers, they also associated condoms with disease. In the early 1940s, penicillin, which was highly effective against syphilis if administered early, was still not readily available in the military. The Army’s only recourse was providing condoms to troops; as many as 50 million were sold or distributed each month during World War II (Brandt 163). Brandt wrote that venereal infections kept many soldiers from the battlefield. While condoms should have been valued as protective, they simultaneously conjured disease and death. Placing the condom in narratives about sex and death associated it with death before a sexual act began. Even if they protected the dutiful soldier abroad and the sanctity of marriage and family at home, many monogamous couples did not think of them as respectable. Once legalized, they were kept behind counters and distributed in discriminating ways. Some couples found them to be too much of a barrier. In 1972, the Medical Aspects of Human Sexuality journal claimed that ultimately, “the condom has never been widely accepted. The educational efforts of the military in World War II had little effect” (Fiumara 146).

Feminism and Its Effect on Condoms

Although the affordability of condoms made them available to all social classes, the condom has also been labeled as a masculine contraceptive device. The women’s health movement attempted to change this by having frank discussions about the condom in OBOS in the early 1970s. The chapter on birth control begins, “Let’s say you want to have sexual intercourse with a man and you don’t want a baby right now – or maybe ever” (Our Bodies, 106). The casual tone stressed that sex was a fun, normal part of life. The book featured a photograph of a condom wrapper next to a rolled-up condom and an unrolled condom. The image was devoid of people, place, and a narrative about intercourse – unlike public health posters and advertisements. The authors discussed the condom’s effectiveness, use, accessibility, advantages and disadvantages. While they were affordable, the authors wrote that “many men say they were embarrassed the first time they bought condoms” (Our Bodies 127). The authors’ tone was candid and opinionated as they explained that the condom “often cuts down on the man’s sensation” and “can irritate a woman” without lubrication.

At the same time, many popular women’s magazines that had previously refused to feature condom advertisements, including Redbook, Ebony, Essence, Saturday Review, Bride’s Magazine, and The Ladies Home Journal, started publishing them (Focus 6). Women’s magazines had reason to be nervous about losing readers: when The Ladies Home Journal discussed venereal disease in 1906, the magazine lost 75,000 readers (D’Emilio 207). Readers were more progressive decades later; the time had come to give women readers frank information about condoms. As Charles Goodrum and Helen Dalrymple argue, “There is little doubt that the advertisers have loved their female audience, but did the writers really know what they were talking about when they created their ads for women?” (249). Feminists reacted to ads with gender biases, including by covering subway ads with stickers that read, “THIS AD INSULTS WOMEN.” Advertising agencies took note and responded, producing checklists regarding how to address content depicting women, with questions like: “Are sexual stereotypes perpetuated in my ad? Are the women portrayed in my ad as stupid? Does my ad use belittling language?” (258). Condom advertisements embraced real women’s concerns by featuring discussion about sexual pleasure and contraception, although male pleasure was still prioritized.

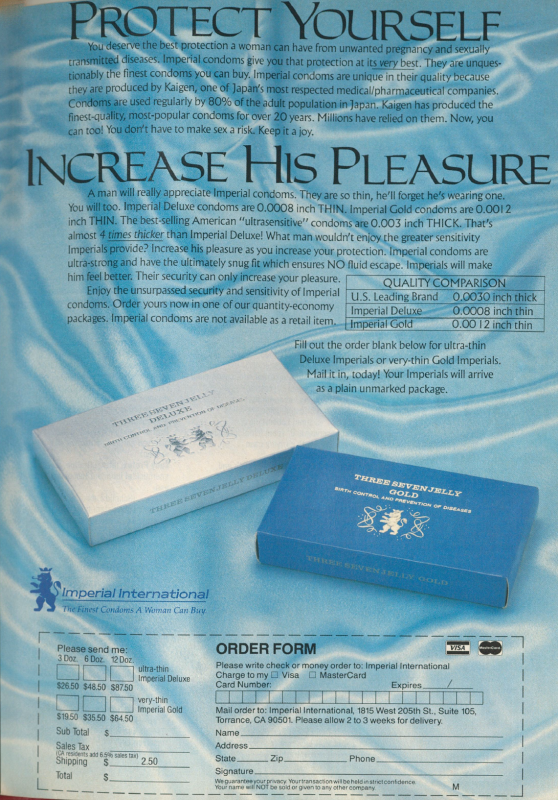

When women’s magazines started featuring condom advertisements, many were accompanied by the word “protection.” In 1986, about 40 percent of condom buyers were women – a 10 percent jump from the decade prior (Wethamer). One September 1987 advertisement for Imperial condoms that ran in Ms. magazine warns the reader to “protect” herself: “You deserve the best protection a woman can have from unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases…You don’t have to make sex a risk. Keep it a joy...Their security can only increase your pleasure” [See Figure 3]. The boxes of condoms are featured against the backdrop of a blue satiny sheet. Although women’s pleasure is mentioned, a man’s pleasure is emphasized with the comment, “A man will really appreciate Imperial condoms. They are so thin, he’ll forget he’s wearing one.” The text suggests that men do not wish to wear condoms so they need to experience sex as though they are not wearing them. The image is similar to the 1940s images in that a man’s point of view is adopted, yet here a woman’s protection is also addressed. The advertisement highlights, “protection, “security,” and “risk”: The “.0008 inch thin” condom was all that stood between a sexually active woman and danger, disease, or even death from the still much-feared and misunderstood HIV. The word “protection” was popular in many of the advertisements in 1980s magazines, from tampons to vacuum advertisements, arguing for a litany of ways in which consumer products could protect women from inconvenient household and domestic disasters. The condom was just another device that would help protect and assist women in their daily lives.

Much of the support for the condom was part of a national public health campaign focusing on AIDS education. In discussing condoms made for women, Mervyn Silverman, head of the American Foundation for AIDS Research, said “Make no mistake about it. Today we have a public health breakthrough. For the first time, American women have a means of preventing HIV in their own control. Never before, not in the 400-year history of the condom, has that been true” (Gladwell). This power shift in sexual health was already embraced by authors of OBOS and Ms., voicing concerns about reproduction, abortion, and sexuality. This victorious narrative can be traced through women’s consciousness-raising groups, health collectives, and health booklets about women’s bodies. At the University of North Carolina, students produced a pamphlet in the 1970 titled, “Elephants and Butterflies…and Contraceptives” to discuss women’s orgasms, side effects of contraception, and local abortion providers (Cohen 203) – a stark contrast to the military’s push to reach men and urge them to use condoms during World War II.

Condoms and the AIDS Crisis

The AIDS epidemic was a turning point for the role of condoms in the national dialogue about sex and disease. When the Centers for Disease Control revealed in 1981 that 26 gay men had Kaposi’s sarcoma, a rare cancer associated with damage to the immune system, physicians reported the cause as a new syndrome, Gay Related Immune Disease, which was changed to Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS). By the following year, physicians identified AIDS in blood transfusion recipients, heterosexual women, young children and intravenous drug users (Brandt 184). The virus is not easily transmitted, and has “been most often spread through sexual intercourse, the most efficient mode of sexual transmission being anal receptive intercourse” (Brandt 185). The attention given to gay men with AIDS enforced a view that gay people were “promiscuous,” as newspapers had claimed throughout the 1970s.

The condom, then, became a pawn in a national moral panic about the sexual morality of gay culture, just as it had been in debates about sexual culture during wartime syphilis outbreaks. Condom use increased along with safe sex programs, but so did homophobia and the link between condoms, disease, and death in the public mind. The condom prevented both conception and disease, but one of these aspects was often emphasized over the other. Joan Beck’s 1992 column “Sexual Devolution in a Litigious Age,” discussed the end of sex as Americans knew it. She wrote about the death of “spontaneous, no-strings-no-consequences, guilt-free sex…not only because of fears about AIDS but, increasingly, because of the possibilities of legal entanglements.” She discussed litigation involving transmission from HIV in the 1990s and argued that people seeking safe sex will need “more than just condoms; they’ll need lawyers” (Beck).

The media debated the stigma of sexually transmitted diseases and the link between condoms and disease. The Plain Truth, a popular Christian magazine, insisted in 1985 that the sexual revolution was over and that “male and female sex organs were made for … holy wedlock and love … not made for lust, perversion or promiscuity” (Schroeder 5)2. A later New York Times Magazine story took issue with the very word “promiscuous,” quoting Berkeley psychologist Walt Odets that “Promiscuity is famously defined as any amount of sex greater than what you are having. Admittedly, it’s an unhelpful word” (Green 42). Attempting to strip the word “promiscuity” of its harm in shaming people also contributed to a safer environment for discussion about sexuality.

Massive sex education efforts came from queer activists in the 1980s. A 1996 New York Times story reported: “In the years after AIDS was first reported, in 1981, the gay community, largely on its own, masterminded what may be the most intensive public health intervention ever … Armed with explicit fliers and scary ads urging the use of condoms for every sexual contact – and later, with subtler messages” (Green 40). Sex education material from the 1980s and 1990s was often intersectional, with depictions of different races, genders and sexual orientations. One pamphlet featured Asian, Black and white parents talking to their sons and daughters about sex (What Parents Need to Tell Children About AIDS). Another pamphlet, which included discussions of anal and vaginal sex, along with sexual practices better known among gay men, including “fisting” and “rimming,” described condoms as “highly effective” against disease (Safer Sex). But sex education material brought backlash, too. When the University of Minnesota made condoms available in university bathrooms in 1987, protestors targeted the Lutheran-Episcopal Center, which co-sponsored the condom-safe week. Episcopal priest Dave Selzer Selzer defended the Center, explaining that sexual responsibility is everyone’s responsibility, noting that unfortunately the condom had an image problem (Scripps Howard). This was a challenge women’s magazines also faced in educating readership about safe sex.

Some magazines did a service to mainstream readership by letting women know that condoms needed to be a part of their lives if they were having sex with men. In October 1988, New Woman published, “10 Ways to Tell a Man He Has to Wear a Condom.” “In a terrifying sense, it is raining outside: AIDS is a threat not only to the main risk groups – male homosexuals, hemophiliacs, and intravenous drug users – but it’s also a serious threat to the rest of the population” (Seeley 103). But not all women’s magazines adhered to this message. A January 1988 issue of Cosmopolitan claimed that women need not worry about contracting HIV, even after having unprotected sex with an HIV-positive man. This led activist filmmaker Maria Maggenti to produce a 23-minute documentary, “Doctors, Liars, and Women: AIDS Activists Say NO to Cosmo.” “Don’t Go to Bed with Cosmo,” a leaflet published by the Women’s Caucus of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP), stated that AIDS was the leading cause of death for women in the New York City area between the ages of 18-34 (Don’t Go to Bed with Cosmo). “This whole movement has very much addressed men’s issues,” activist Rebecca Cole said. “There needs to be leadership now in [the] media and whatnot addressing the fact that women are at risk and not invisible.” In 1991, the AIDS activists’ effort to persuade the Centers for Disease Control’s to expand the definition of AIDS, so that more women could get health benefits, featured a poster that read “Women Don’t Get AIDS/ They Just Die From It (Schulman).”

Despite the overall attitude shift toward condoms, a conservative presidential administration objected to their proliferation. In 1987, President Ronald Reagan’s administration decided against making condoms available in federal prisons (“U.S. Rules Out Condoms”). Reagan’s speechwriter Pat Buchanan, said, “The poor homosexuals – they have declared war upon Nature, and now Nature is exacting an awful retribution” (Brandt 193). While some heterosexual couples relied more on condoms during and after the AIDS crisis, many men were still resistant to using condoms, and some women found the topic challenging to bring up with their partners (Gordon 471).

Women’s sexual health quickly became the focal point for mainstream magazines covering AIDS. The number of women with HIV increased rapidly in the 1980s, with HIV having a “major impact on morbidity and mortality among young women.” By 1987, AIDS was the eighth leading cause of death in women ages 15 to 44 (Ellerbrock et al 2971). Basketball star Earvin “Magic” Johnson’s claim that he contracted HIV through sex with women also contributed to anxieties about the spread of HIV, a claim that reproduced the wartime condom poster’s hidden curriculum: that women were contaminators. TIME magazine asked in 1991: “How easy is it to get AIDS from straight sex? How fast can it spread? Could an AIDS epidemic like the ones sweeping through the Third World nations take root in the general U.S. population as well?” (Elner-Dewitt 72). These questions evinced national anxieties about the future of American heterosexual couples. By diverting attention from the gay community, magazines reinforced the importance of white women’s reproductive potential. In his 2004 book No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive, Lee Edelman outlined the ways in which reproduction represents a bountiful future against which gay men and lesbians are positioned in culture. This idea can also be traced through condom discourse that privileged empowerment of heterosexual women.

As women became a target for AIDS education, advertisers responded. Gordon argued that the AIDS crisis led to condom advertising being aimed primarily at women. “The breaking of taboos, silences about sex, that the advertising necessitates seems likely to further the general cultural movement toward more explicitness about sex” (Gordon 471). A 1995 issue of Family Planning Perspectives found that condom advertisements and HIV public service announcements seemed “to be disproportionately aimed at women.” Sociologist Janet Lever argued that “their content reveals two underlying assumptions – namely, that women are likely to encounter male partners who resist using condoms, and that women have enough power in their sexual relationships to overcome that resistance” (Lever). What Lever argued, many others did too: that men and women did not possess equal power in choosing contraception (Roberts and Crawford 273). This was why HIV/AIDS educational materials aimed at heterosexual women promoted assertion in sexual encounters.

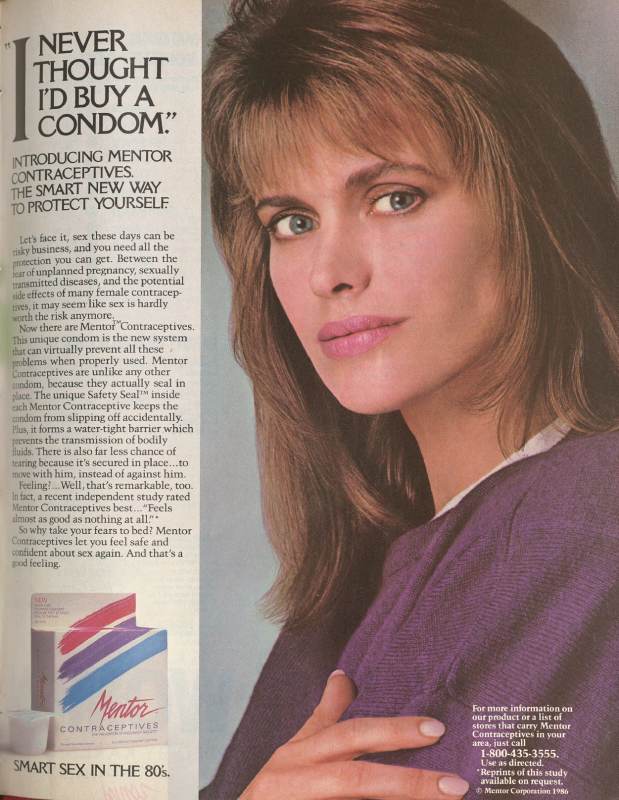

Communications scholar Tom Reichert argued in The Erotic History of Advertising that Durex condoms made sure its advertisements appealed to both women and men since women have been a growing group of condom purchasers. “Gone are the ads appealing to male egos such as ‘the big score.’ In are the ads emphasizing pleasure, romance, intimacy, and good sex,” Reichert argued (329). The “I Never Thought I’d Buy a Condom” advertisement for Mentor condoms, which ran in Ms. in August 1987, features a white woman with her arms crossed, staring out at the reader. She is wearing pastel clothing that mirrors the feminized colors of the condom packaging. This condom was packaged in a small white, purple, and mauve plastic cup and sold in the feminine hygiene sections of pharmacies (Mall). The ad copy reads: “Let’s face it, sex these days can be risky business, and you need all the protection you can get…why take your fears to bed? Mentor Contraceptives let you feel safe and confident about sex again. And that’s a good feeling” [See Figure 4]. This woman’s protection is linked to her pleasure – “a good feeling” – that safety and pleasure are inextricable and together made for better sex.

A similar advertisement for Trojan that ran in a March 1987 issue of Vogue featured a white woman in business attire, claiming: “Very often, the best contraceptive for a woman is the one for a man … What would be the best contraceptive for a woman? … Get ready for a little surprise … It’s the Trojan condom … They’re completely without serious side effects … They’re easy to buy … But there’s even more. The condom helps reduce the risk of spreading many sexually transmitted diseases.” The young woman wears light makeup, stud earrings and a buttoned-up shirt and suit jacket. She is a working woman – her pose and physical presentation is even similar to the 1940s poster “She May Look Clean – But.” Both of these ads are preoccupied with claiming the condom as a woman’s contraceptive device, despite the condom’s historical association with male soldiers. Instead of featuring women as dangerous, these magazine advertisements positioned women as agents encountering danger. Women’s magazines embraced a public health angle to make the condom more socially acceptable. They also featured only white women, despite mainstream and African-American women’s magazines covering AIDS as an increasing threat to Black women (Whetstone). Tiffany Rogers wrote a thesis about how contraceptive ads for Cosmopolitan and Essence magazine differed in the way they appealed to Black and white women between 1992 and 2012. Black women were shown ads for doctor-administered birth control such as injections, implants or IUDs, not condoms (45). Rogers’ findings illustrate that Black women were ignored by condom advertisements. The hidden curriculum here is one in which doctors continued to control the reproduction patterns of Black people. Whiteness, as Dyer argues, was depicted as representing ordinariness (222). Because condoms are a contraceptive method, controlled by the engaging partners – not doctors or outsiders – they were marketed to white women, not Black women. This is another layer in which condom visual culture reflected dominant social norms.

Women’s magazines may have felt as though they had to be careful. They had already positioned themselves as champions of the 1980s woman, taking back power during uncertain times. Photographs of the condoms themselves may have seemed too suggestive, too male, or too phallic. Condoms still had a negative reputation among conservative groups against sex education, even during public health campaigns. Sally Beach, a Palm Beach, Fla. anti-abortion activist, claimed in 1986 that “I feel that we are handing children condoms before they are even getting crayons out of their hands and that’s certainly giving them a message” (Wiggis).

Instead of rendering them as the gateway to sex, women’s magazines framed condoms as sources of protection and pleasure. Advertisements of 1980’s condoms focused on protecting white, middle-class women with purchasing power from disease and unwanted pregnancies, but the advertisements also took their cues from pro-sex feminism of the 1970s and 1980s by emphasizing women’s pleasure. The “protect yourself, increase his pleasure” advertisement demands that the sexual experience be a satisfying one. Although the male pronoun makes it into the slogan, the women’s pleasure, too, was addressed: the Imperial condom was so effective that women would experience a new sense of “security” that would also bring her “pleasure.” Even in the ads marketing to women, their pleasure was seen not through the lens of sexual gratification but through the security of an effective and safe condom. The “I Never Thought I’d Buy a Condom” Mentor ad emphasized a “remarkable feeling,” touting the pleasureful potential of the condom’s “water-tight barrier.” Although the condom was no panacea, it allowed men and women more sexual freedom. Studying visual culture reveals that the condom was finally deemed more socially acceptable by the end of the 20th century. Together, images in poster campaigns and advertisements illuminate the ways in which the condom stood for contrasting symbols to people with the power to shape national understanding of birth control, the body, and sexuality. While the earliest images promoting condoms depicted an overtly feminized and misogynist caricature of women’s lascivious sexuality, later images were more considerate of real women’s needs and concerns.

Figure 1. “She may look clean but.”

1940. University of Minnesota Libraries, Social Welfare History Archives, umedia.lib.umn.edu/item/p16022coll223:8, Accessed 26 Jun. 2024.

Figure 2. You may think she's just your “gal”

1944. University of Minnesota Libraries, Social Welfare History Archives, umedia.lib.umn.edu/item/p16022coll223:79 Accessed 26 Jun. 2024.

Figure 3. Imperial condom advertisement

Ms. magazine. September 1987, p. 101.

Figure 4. Mentor Contraceptives condom advertisement

Ms. magazine. August 1987, p. 163.